Think about Fukushima Disaster

Part 4: What Can We Learn from the Tsunami?

The east side of Fukushima Prefecture faces the Pacific Ocean, and the coastline is approximately 166 km long. The series of tsunamis triggered by the Great East Japan Earthquake inundated 112 square kilometers, or 5% of the area of the coastal municipalities in Fukushima Prefecture.

The ocean, which brings us so many blessings, has shown us the threatening side of nature. The tsunami that destroyed all the power sources of the nuclear power plants and caused the long-lasting accident in Fukushima was over 15 meters high, almost three times higher than expected.

As we are now being urged to strengthen our countermeasures against natural disasters and conserve natural resources, there are many lessons to be learned from this disaster.

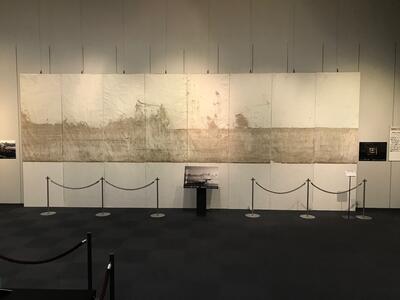

Tsunami traces on the wall

Minamisoma August 10, 2012

Wallpaper with reinforced backing reproducing the height of the tsunami traces

Minamisoma collected on September 17, 2012

“Yossi Land" is a nursing home located about 2km inland from the coast in Haramachi Ward, Minamisoma City. At the time of the disaster, there were about 140 patients and 60 staff members in the building. Even though this location was not included in the tsunami hazard area on the city's hazard map at the time, it was hit by the tsunami and 37 people were killed. The interior walls of the building were covered with traces of the tsunami that were over two meters high.

The building was demolished the following year and moved to a different location. The curator of the Fukushima Museum went to the site and photographed all the walls. The wallpaper was removed and preserved, and the back of the walls were reinforced with paper and boards so that the traces of the tsunami could be reproduced at their actual height. The traces of the tsunami convey to us its power with more reality than photos or videos.

Tsunami-damaged road sign

Minamisoma May 26, 2014

Verification of the broken part of the road sign

Minamisoma May 26, 2014

Asphalt road surface rotated by the tsunami

Minamisoma July 13, 2014

A road sign indicating a "curve ahead" had fallen on the side of the road on Prefectural Road 391, which runs near the coast in Odaka Ward, Minamisoma City. By matching the cracks in the base post left by the roadway with those in the sign, we found that the sign, made of aluminum alloy plate and galvanized steel pipe, had been bent by the force of waves coming in from the sea toward the land, and then folded by the receding tsunami wave.

More surprisingly, near where the sign stood, a 25-meter section of the asphalt road surface was displaced and rotated clockwise by the impact of the tsunami. Part of the edge of the road surface was wedged into the base of the sign. These objects convey the terrifying power of the tsunami.

Tsunami-devastated police car

Tomioka June 11, 2014

Damaged patrol car door

Tomioka collected on January 15, 2015

Police car interior equipment

Tomioka Collected on March 5, 2015

Immediately after the earthquake, two police officers from Futaba Police Station, located in Tomioka Town, rushed to the coastal area in a patrol car, Futaba No. 31, to guide residents to evacuate. The police car was then hit by the tsunami and was found near a bridge at the mouth of the Tomioka River with a large amount of earth and sand flowing into the car. The body of one of the police officers was found at sea about a month after the tsunami, while the other remains missing.

Deployed to Futaba Police Station in 2003, this Toyota Crown patrol car was involved in many duties to keep residents and the community safe. Inside the car, there were tools used in daily operations such as chalk for drawing white lines and cassette tapes of traffic safety campaigns, as well as microphones used to call for evacuation. The key was still plugged into the car's ignition.

In 2015, the main body of this police car was moved to a park next to the Futaba Police Station. In front of the police car, flowers were continually offered in memory of the police officers who sacrificed themselves to save the residents. This police car is now on display at the Tomioka Archive Museum, which has opened in 2021.

Mizuaoi in Murakami district, Odaka Ward

Minamisoma July 14, 2016

Solar panels were installed after the construction of the seawall in Shimoshibusa area

Minamisoma February 15, 2019

Specimen of Mizuaoi

Minamisoma collected on September 19, 2014

Coastal areas inundated by the tsunami returned to their former landscape before land reclamation, and in some places, the water did not recede for a long time. In these places, one of the plants that can be seen again is the beautiful blue flowering Mizuaoi (Monochoria korsakowii).

The Mizuaoi is an aquatic plant that grows on the margins of rivers and reservoirs and blooms from August to October, and was once a common plant in coastal alluvial areas. However, due to river improvement works and the use of pesticides, they gradually disappeared, and in 2002, the Red List issued by Fukushima Prefecture designated them as "Endangered II", meaning "a species with an increased risk of extinction".

As the soil was disturbed by the tsunami and the wetlands area expanded, the Mizuaoi woke up again, and for a while, colonies of this plant could be seen in many places. Their lovely appearance after the tsunami seemed to be a symbol of revival. The Disaster Heritage Preservation Project, for which the Fukushima Museum served as the secretariat, paid attention to this Mizuaoi and held a study session and field trip in 2016 as an outreach project to learn about the changes in the natural environment after the earthquake.

However, due to the subsequent reconstruction and embankment construction work, it has become difficult to see the Mizuaoi again. In the 2020 edition of Fukushima Prefecture's Red List, the Mizuaoi is still listed as "Endangered II". The momentary appearance and disappearance of the Mizuaoi colony raises many questions about the natural environment and human activities.

Special cooperation by MALY Elizabeth

Part 3: The Clocks are Pointing at That Time

Following the 9.0 magnitude earthquake that struck off the Pacific coast of Tohoku at 2:46 p.m. on March 11, 2011, the Pacific coast was hit by a massive tsunami with waves over 10 meters high in some places.

The clocks left at the disaster site indicate the time when the place was hit by the earthquake, tsunami, or another calamity, telling a different story of the situation they were in.

Clock of Michi Beauty Salon

Tomioka Collected on March 6, 2015

Now on exhibit at The Historical Archive Museum of Tomioka

Michi Beauty Salon damaged by the earthquake and tsunami

This clock was hanging in the storefront of Michi Beauty Salon, which was located in the shopping district near Tomioka Station on the JR Joban Line. This electric clock stopped due to a power failure immediately after the earthquake. The time on the clock was about three minutes later, because the owner had set the clock ahead beforehand.

After the earthquake, the coastal area of Tomioka was hit by a tsunami up to 21.1 meters high, and the area near Tomioka Station was also inundated. Michi Beauty Salon, located about 200 meters from the shore, was also covered by the waves, and this clock, which was hung higher than a person's height, has stains on it that appear to be from the spray of the tsunami.

Clock of Igari Barber Shop

Tomioka Collected on October 21, 2015

This is the clock of the Igari Barber Shop, located in Obama, Tomioka Town, about 500 meters from the coast. According to the owner, the clock had originally been set forward by nearly five minutes. The clock, which is electrically operated like the one at Michi Beauty Salon, stopped due to a power outage a few minutes after the earthquake, and the hands are still pointing at that time.

Clock of Toyoma Junior High School Gymnasium

Iwaki Collected on December 10, 2015

This is a clock in the gymnasium of Toyoma Junior High School in Iwaki City. After the earthquake, the Tairausuiso district, where the school was located, was hit by a tsunami up to 8.5 meters high. 87% of the houses were completely destroyed, and 65% of them were washed away. The death toll from the tsunami was 111, the worst in Iwaki City.

The students and teachers of Toyoma Junior High School were among the first to evacuate and escaped the disaster, but the first floor of the school building was flooded. The hands of this electric clock pointed to 3:27, the time when the tsunami reached the school and caused the power outage.

The Toyoma Junior High School building was demolished in 2015 and is now used as a green space for disaster prevention.

Exhibition at the Fukushima Museum

Aizuwakamatsu January 2021

Since the Great East Japan Earthquake, the Fukushima Museum has been holding exhibitions of Disaster Heritage. Some of the visitors are victims of the disaster or people who are related to the materials, and they sometimes give us new information, such as details of the materials and what they were like before the disaster, which we did not know when we collected them.

Many of the things that occurred in the confusion of the combined disaster of the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear power plant accident will fade away and be forgotten unless someone actively tries to preserve them.

It is one of the important roles of a museum to collect, preserve, and pass on to future generations the materials and information that represent "that time”.

Special cooperation by MALY Elizabeth

Part 2: The Disaster and Animals

Interior of a barn at the Hangui Farm

Minamisoma March 18, 2016

It is not only humans who are affected by major disasters, but animals were also in danger of dying as well.

After the accident at TEPCO's Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011, the area within a 20 km radius of the plant was declared an "exclusion zone" and all residents were forced to evacuate.

Before the accident, there were about 300 cattle farmers in the area, raising about 3,500 head of cattle. There were also nine pig farmers, raising about 30,000 pigs, and nine chicken farmers, raising about 440,000 chickens.

One of the cattle farmers, Mr. Issei Hangui of Hangui Farm, who was 61 years old at the time of the earthquake, had been running a dairy farm in Odaka Ward, Minamisoma City for 40 years and was raising 40 dairy cows at the time. His dairy farm was also severely shaken by the earthquake, but was not damaged by the tsunami. However, when the nuclear power plant had an accident, they were also forced to evacuate 19 km away from the plant. They left their cows behind, which were like family to them.

Issei Hangui, the owner of Hangui Farm

On March 15, he decided to evacuate, first to Haramachi Ward, where his daughter and her family lived, and then to Fukushima City, where his son and his family lived. He thought he would be able to return soon, but he was not allowed to enter the farm without permission. Out of responsibility to the community, he closed the shutters of his barn when he evacuated because he was concerned that the cattle would damage the neighboring houses and fields.

It was unthinkable for a cattle farmer to leave his cows behind. Even at the evacuation site, he couldn't stop thinking about the cows and couldn't stop crying when he remembered them.

Cowshed at the Hangui Farm

Minamisoma March 28, 2018

It was on June 10 that he opened the shutters of the barn again. This was the first time he had received permission from the prefecture. When he opened the shutters, his vision was blackened with flies and maggots as high as cow carcasses were buzzing around him. He was so shocked that he could not even cry.

It was the end of August when he noticed something strange about the pillars in the barn. The temporary burial of the dead cows had been decided, and he was working with his cattle farmer friends and the construction company to pull out the dead cows. They knew immediately how it happened. The starving cows were so hungry that they bit into the pillars. Everyone was shocked into silence.

Replica of a barn post gnawed by a cow, created in March 2019

At the Fukushima Museum, we made a replica of the pillar of the barn at the Hangai Farm. It was created in March 2019, using a mold taken from the actual pillar of the Farm. This material is being used in exhibitions and educational activities as one of the materials to tell the story of the nuclear power plant accident and as a Disaster Heritage to consider the theme of "life”.

This material was also used in the projects of the Life Museum Network Executive Committee, of which Fukushima Museum is the secretariat, and was exhibited at ICOM Kyoto 2019 as part of the report on the results of the project, which was also seen by museum professionals from around the world.

Exhibit at ICOM Kyoto 2019

September 2, 2019

Special cooperation by MALY Elizabeth

Part 1: What Happened in Fukushima, and What Is Left Behind?

Ships washed ashore by the tsunami

Minamisoma March 12, 2011 Photo by Ohtsuki Akio

Preface

The 9.0 magnitude earthquake and resulting tsunami that struck on March 11, 2011 caused tremendous damage to Fukushima. The next day, there was an explosion at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant managed by TEPCO. This was the beginning of the nuclear disaster, which caused special circumstances in Fukushima.

Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima are known as the three disaster-stricken prefectures. In Fukushima, however, the aftermath of the disaster spilled over into many other things, and unexpected incidents continued to occur, leading to a unique situation. Words such as "town-wide evacuation," "decontamination," "radiation measurements," "becquerel," and "sievert," which we had never heard of or used in our daily lives before the disaster, have become commonplace.

Vehicles carrying contaminated soil

Futaba March 15, 2018

A variety of things related to the disaster have accumulated over the past ten years. At the same time, recovery, return, and reconstruction have progressed, and new landscapes have been created, but they have become so ingrained that we don't even realize that they were triggered by the 2011 disaster.

Instead of recovering to the life we should have had, we were forced to accept a daily life with different aspects. This emergence, continuation, and establishment of the extraordinary, in other words, the transformation of the “unusual” into the "usual," can be said to be the ten years of Fukushima.

Under these circumstances, how should the Fukushima Museum, a regional museum in the disaster area, have faced the disaster and what should it have done? One of the actions taken to answer this question was the Disaster Heritage Preservation Project that started in 2014.

Train tracks washed away by the tsunami

Kegaya, Tomioka June 27, 2016

The Role of the Museum and the Launch of the Disaster Heritage Preservation Project

One of the activities of the Fukushima Museum in response to the Great East Japan Earthquake is the Disaster Heritage Preservation Project, an effort to create a museum resource of the disaster.

As a regional museum, the fundamental role of the Fukushima Museum is to collect, preserve, research, and exhibit materials related to the history, culture, and nature of Fukushima, and the museum has the organization, functions, and facilities to realize these roles.

Positioning the disaster as a stage or turning point in history and questioning what the disaster was is truly constructing history, which is in line with the purpose of the Fukushima Museum. In order to do so, what this project should do is to clarify what happened to the region of Fukushima and the people living there during this disaster, and to create methods that can be shared beyond the region and passed on to the next generation.

Active fault that appeared after the earthquake

Iwaki July 3, 2014

Immediately after the earthquake, the museum focused on rescuing cultural properties. On April 22, 2011, the area within a 20km radius of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant was declared an "exclusion zone". In that area, there were a number of thefts, cultural properties were under unattended, and there were even power outages. These were major problems for the protection and management of cultural properties.

The Agency for Cultural Affairs and the boards of education of prefectures, cities, and towns conducted on-site inspections, and in May 2012, a rescue headquarters was established to confirm the process of cultural property rescue in the exclusion zone. In August, measurement of radiation levels of cultural properties and packing of materials started in Futaba, Okuma, and Tomioka Towns, and the first removal of materials from the exclusion zone was carried out on September 5. In this way, the procedure of how to rescue cultural properties in the evacuation area was established.

Collect materials

Namie September 31, 2014

Museum curators went into the exclusion zone to directly check the level of radiation in the air and the situation there, and to share information. The rescue project also provided an opportunity for the curators and the local government officials to consider how to preserve the materials generated by the disaster. In November 2012, an internal meeting at the museum proposed that such materials should be collected, and the project was approved in April 2013. A working group was organized and started to discuss the details of the project.

We discussed how to position the project as a museum, the framework of Disaster Heritage, the organization and structure, and the storage location, and also confirmed the intentions of organizations that might be able to cooperate. We toured the coastal areas to see what was available in the affected areas, and collected information on disaster exhibition facilities. Budget negotiations were difficult, but as a result, we received a subsidy from the Agency for Cultural Affairs and decided to set up a new executive committee to implement the project. The subsidy from the Agency for Cultural Affairs lasted until 2017.

At a meeting in January of 2014, the concept of "Disaster Remains" was presented. It is essential for this project to have a perspective of what is in what place, and an archaeological framework is useful for this, and the concept of "War Remains" was referred to. It was finally decided to call the materials created by the earthquake disaster "Disaster Heritage”.

Tsunami marks on the wall

Minamisoma August 10, 2012

Passing on the Great East Japan Earthquake and Disaster Heritage

The Great East Japan Earthquake is said to be a disaster of unprecedented scale. Specifically, it was a large-scale, widespread, and long-lasting disaster. Under these circumstances, each individual, family, organization, and community that faces the disaster will create their own experiences and events, forming the "Fukushima experience”.

The term "complex disaster" or "multiple disasters" is often used to describe the situation in Fukushima. The earthquake off the coast of Tohoku triggered a massive tsunami, which in turn led to the nuclear power plant accident. There were human casualties, life crisis, collapsed houses, debris accumulation, and the spread of radioactive materials and anxiety about them, all of which were caused by these three factors. The first stage of the response was rescue, evacuation, and support, followed by the second stage of recovery, reconstruction, decontamination, and return.

A characteristic of Fukushima is that the various stages and phases of damage and response are occurring simultaneously. Each of these aspects was created by the disaster and constitutes the "Fukushima experience". By looking over these aspects, we can see the regional differences and compare and examine them. In each phase, there is a Disaster Heritage that reflects and symbolizes Fukushima's post-disaster progress.

A police car damaged by the tsunami

Tomioka June,11 2014

Disaster Heritage is the historical material that represents the "Fukushima experience," the "objects" and "places" that were produced by the Great East Japan Earthquake and that represent the disaster itself. The following four types of material are considered to be the most concrete examples of Disaster Heritage.

1. Traces of earthquakes and tsunamis - cracks in the ground, faults, tsunami deposits, etc.

2. Damaged objects, i.e., things that were damaged or lost their functions due to the disaster - rubble and damaged buildings

3. Things that were built or used in response to the disaster, and landscapes that were created - temporary housing, accumulation of flexible bags used to hold contaminated soil

4. Things that lost their original meaning due to the disaster - posters for events that would have been held if not for the disaster

In addition, there are some Disaster Heritage objects that cannot be classified into any one category, but have multiple characteristics.

Post boxes washed away by the tsunami

Tomioka Collected on March 5, 2015

The "objects" and "places" that are positioned as Disaster Heritage are rapidly disappearing due to the activities of nature and disposal as unnecessary items. In addition, as long as the response to the disaster continues, Disaster Heritage will be produced in a variety of aspects, and will not be something that is created in a single moment immediately after the disaster. In other words, they have been repeating the cycle of production and extinction over the past ten years. It is the role of museums and the position of the project to place the perspective of "preservation" in this continuous cycle and transform symbolic Disaster Heritage into historical materials.

Gallery talk at Fukushima Museum

Aizuwakamatsu March 11, 2019

More than 2,000 items of Disaster Heritage have been collected so far. In 2021, a new division of Disaster was established at the Fukushima Museum. The team, led by disaster experts, will collaborate with the local community and share knowledge and experience, aiming to make the museum a place where local people can think proactively about their lives and use them for the future.

Special cooperation by MALY Elizabeth

|

〒965-0807 <お問い合わせフォームは こちら > |

福島県立博物館

福島県立博物館